|

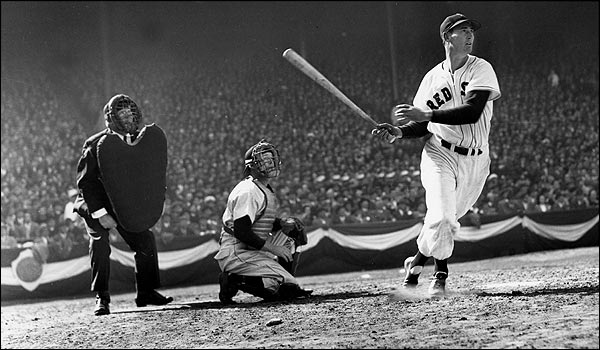

| (Brearley Collection Photo from Opening Day 1947) |

By Lew

Freedman | Staff Historian

He refused

to tip his cap to the fans after the last majestic hit of his wondrous 21-year

Major League career with the Boston Red Sox. He refused to step out of the

dugout to acknowledge the cheers filling the air at Fenway Park in the last

game of his professional life. And that was so Ted.

The

ballplayer who said his only ambition in life was to have people see him walk

down the street and say, “There goes the best hitter there ever was,” achieved

his goal and slipped away from his sport on his own terms.

Ted Williams

may well have been the best hitter in baseball history, although some can argue

statistics for Ty Cobb, Rogers Hornsby or Babe Ruth, those who like Williams

are in the penthouse of the Hall of Fame.

It is 52

years since Williams retired his Boston Red Sox spikes on September 28, 1960,

as was true throughout most of his career, they were going nowhere but home as

the regular-season ended. Williams saw too few Octobers in his career with the

Red Sox.By October, rather than watch those annoying New York Yankees play in yet another World Series, Williams had retreated to one of his favorite haunts to pursue one of his favorite pleasures, fishing for Atlantic salmon, tarpon, or bonefish. It would be too much of a cliché to say that this was Williams’ relaxation because he fished with the same aggressive attitude that he brought to the batter’s box. Also a member of the Fishing Hall of Fame, Williams was just about as good at it as he was hitting. He once caught a 1,235-pound black marlin off the coast of Peru that would not have fit into his Fenway locker.

Reaching the

majors in 1939, Williams was the rare player whose career touched four decades.

He was 42 in 1960 and would have given up his left-field perch a year sooner,

except that he was disgusted with his 1959 showing when he hit just 10 home

runs with a .254 batting average. That was not the Ted Williams he wanted

people to remember.

Even

Williams was astonished by his tumble since he was coming off two seasons, 1957

and 1958 when he batted .388 and .328 respectively, and won the American League

batting title for his fifth and sixth career championships. A less-confident

individual would have heeded the .254 as a warning signal that he had

overstayed his welcome, but Williams took it as a challenge.

The man who

had the eyesight of an eagle, who could pick up the spin of a 90-mph fastball

in the split second after it left the pitcher’s hand, did not want to admit he

might be trapped in athletic old age. That 1960 season Williams smacked 29 home

runs and batted .316.

When Ted

Williams was a baseball prodigy coming out of San Diego, his first Boston

teammates, who found him to be insufferably cocky, called him “The Kid.” He

stood 6-foot-3, but seemed taller because his weight was stuck somewhere in the

170s before filling out to a muscular 205. The nicknames piled up over time and

Williams was called “The Splendid Splinter,” “Teddy Ballgame,” and “Thumper.”

If there was

annoyance among veterans because Williams had a big mouth it did not take long

to show there was heft to his braggadocio. As a 20-year-old he batted .327 with

a league-leading 145 RBIs. The next year he hit .344, which coincidentally

would end up being his lifetime average. In Williams’ third season, 1941, he

batted .406. Anyone who bats .400 in the majors is in very elite company and no

one has done it in the 71 years since Williams.

There was no

designated hitter in the American League in 1960, but one must wonder if there

had been, if coming off a near-30-homer, .300-plus season would Williams have

stuck around another year. It would have been tempting for a player who loved

hitting far more than other facets of the game. In his younger days Williams

used to stand in the outfield and take imaginary swings. To him, it seemed,

fielding was an obligation that inconveniently interrupted his at-bats.

It wasn’t as

if staying around another season would give Williams another chance at a World

Series. During his long career the Red Sox advanced to just one Series, in

1946, and lost it in seven games to the St. Louis Cardinals. The Red Sox

finished 24 games under .500 in 1960 and 10 games under in 1961.

The official

announcement of Williams’ retirement was made with three home games left

against the Baltimore Orioles and three games on the road against the New York

Yankees.

The Red Sox

knew they should do something special on the cold, damp end-of-homestand 28th,

but Williams did not want a fancy farewell party. Broadcaster Curt Gowdy said

his piece and in Williams’ name Boston Mayor John Collins presented a check to

the Jimmy Fund, the organization long associated with helping children with

cancer.

Williams did

not make a full speech to the 10,454 fans. He offered a few brief remarks, then

it was Play Ball!

Williams

walked in the first inning and scored on a sacrifice fly, and he flew out to

center in the third. In-between innings, it was announced that after this game

Williams’ No. 9 Sox jersey would be retired. That meant Williams was not going

with the team to New York. This was his last game. Williams lined out to right

field in the fifth inning.

When Williams moved

into the batter’s box in the eighth inning, fans gave him a two-minute standing

ovation. Williams ignored it and focused on Orioles pitcher Jack Fisher. On a

1-1 pitch, Williams connected, sending the ball 440 feet into the right-field stands.

With his

long stride, Williams made it around the bases swiftly. He didn’t look up, but

did complete a congratulatory handshake with Sox catcher Jim Pagliaroni, the

on-deck hitter, as he reached the plate.

With his

long stride, Williams made it around the bases swiftly. He didn’t look up, but

did complete a congratulatory handshake with Sox catcher Jim Pagliaroni, the

on-deck hitter, as he reached the plate. Williams ran straight into the Red Sox dugout as the crowd, on its feet again, roared and applauded. The ovation was clocked at four minutes, an eternity in such a situation, but Williams, despite the urgings of his teammates, would not step out of the dugout to wave.

In a famous bit of prose summing up the day, author John Updike, writing for The New Yorker, said, “Gods do not answer letters.”

Over the

years, Williams had been prickly, irritated those fans, feuded with the press,

and was not ready to let-bygones-be-bygones mood. As he aged, however, he

mellowed, becoming more cooperative with future generations of reporters,

taking a stand demanding that the Hall of Fame open its doors to the best

African-American players shut out of the majors by discrimination.

At the

All-Star game of 1999, played at Fenway Park, Major League Baseball announced

its all-century team. The grandest ovation was saved for Ted Williams, driven

in a golf cart to the mound to throw out the first pitch. The modern-day All-Stars

mobbed Williams and brought tears to his eyes.

“Wasn’t it

great?” Williams said. And then he launched into praise of Boston fans, saying

the team was lucky to have them and calling them “the best.”

It was the

speech he might have made in 1960.

On his

circuit around the field in the cart, as the fans stood and cheered, Williams

removed his hat and waved it high in the air, over and over again. It took a

half century, but Williams had at last doffed his cap to his fans.

Lew Freedman has authored 54 books, including a biography

with Juan Marichal, a biography with Ferguson Jenkins, and several works

of baseball history, including Going Yard: The Everything Home Run

book in cooperation with Frank Thomas, and Hard-Luck Harvey Haddix and

the Greatest Game Ever Lost.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment